SCUBA DIVER An under-the-sea adventure with double Q-learning!

Technical Description

Project Summary

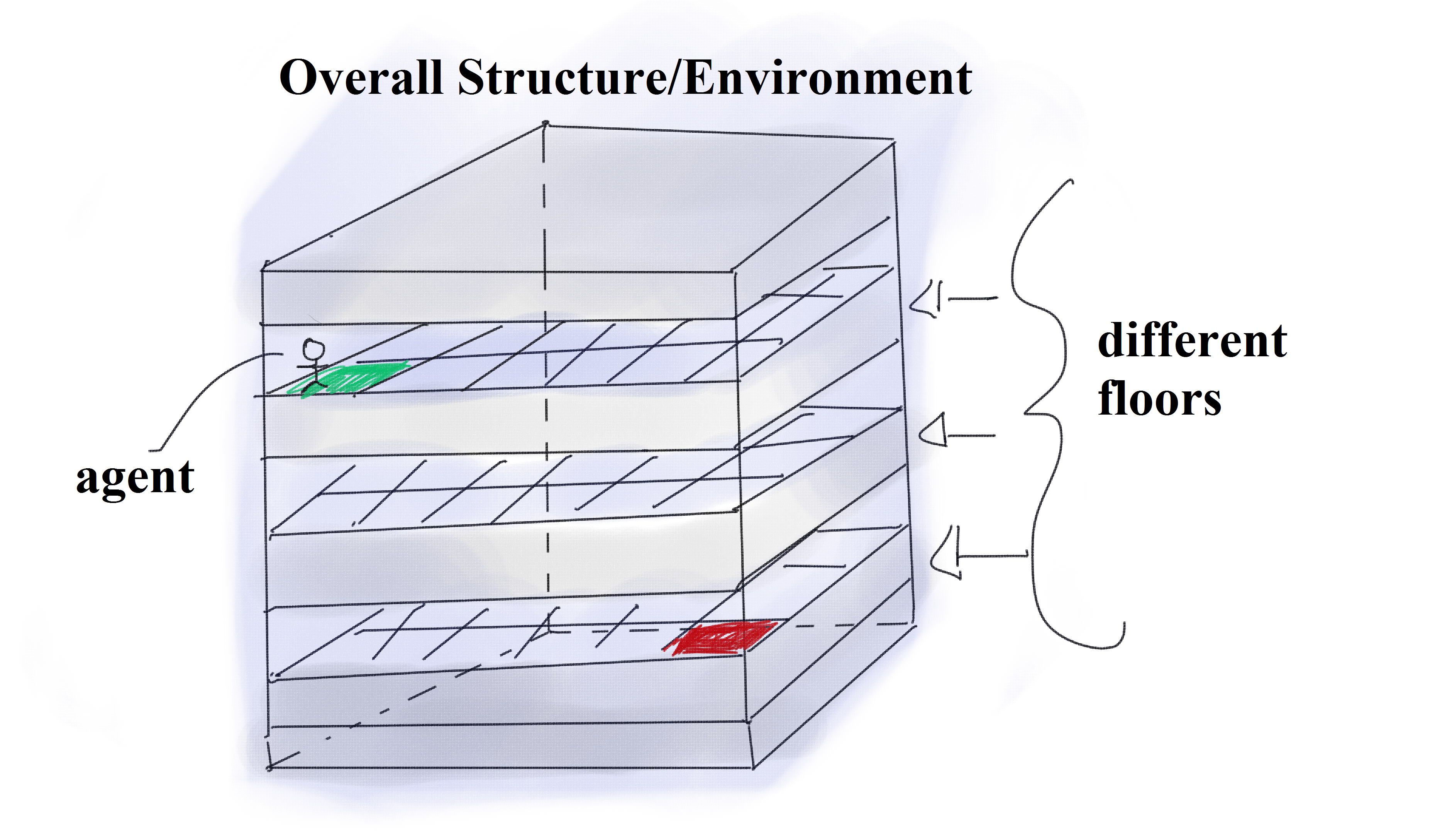

When we first began formulating an idea for the project, we initially wanted to teach the agent to learn how to shoot a bow and air efficiently using a convolutional neural network. We dove in head first trying to learn all we could about how to use a CNN with Minecraft. However, as time progressed, we began to see we were way out of our depths in terms of knowledge about an already very complex model. So, we had to reevaluate our goals and decided it was best to reduce the complexity of our project but still have an interesting idea to apply to Minecraft. With the class being about reinforcement learning, we thought it would be a cool idea to use Q-learning as the basis of our project. The general idea is to use a single Q-learning algorithm and let the agent learn and gather data. Then, we will implement double Q-learning algorithm to fix the inefficiencies with just a single Q-learning algorithm. Once this is done we will make a comparison of the two types, highlighting the pros, cons and differences between them. A more general explanation of our new project from the Minecraft perspective is an agent that explores a 3D underwater maze in search treasure but with a limited amount of resources. This might sounds like assignment 2 but there are some key differences to which we apply the algorithm and variables that provide for some very interesting problems. The first problem being that to navigate a 3D maze, we must allow the agent to move in 3 dimensions. Instead of having the 4 standard states (forward, backward, left, right), we now have 6 states which includes moving up and moving down. The second major difference is that we introduced a new resource that needs to be managed by the agent in the form of air. Now, the agent has to decide whether it has enough air to keep exploring and find more treasure or to reach the goal without drowning. Currently, our group is testing the agent with only two floors enabled because it is more efficient for testing our algorithm and it has a state space large enough for us to understand its scale but small enough so that it won’t take us a long time to get the agent to final goal.

Approach

Before discussing the main algorithm we will be using to train our agent, let’s look more in depth at our MDP:

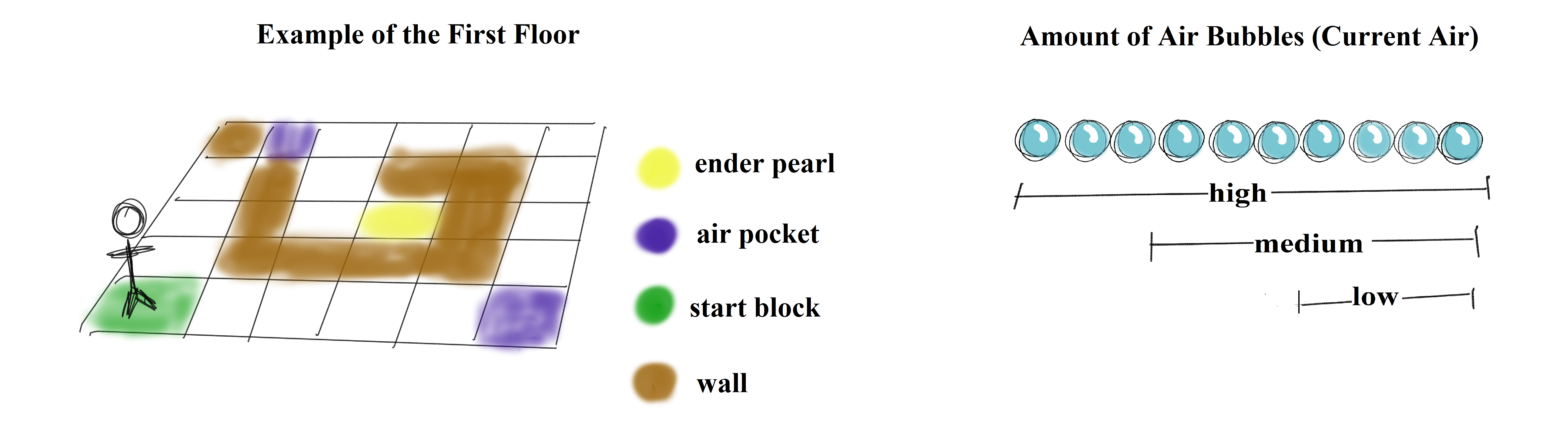

Our agent explores a custom made map that is based on the deep sea biome environment. Since the environment is 3-Dimensional, the state of our agent will be represented by its current (x,y,z) location in the Minecraft map. In addition, because our agent needs to keep track of how much air it has left, we will associate the amount of breath it has with the following keywords: “high”, “medium”, “low”. So an example of a state may be x=”1142.5” y=”25” z=”-481.5”, breath=”high”. With this, you can see that even in a small environment, say a 5x5x5 cube of water, the size of our state space quickly heightens to 375 different states (555*3). However, having wall-like structures to create mazes decreases the locations in which the agent can travel to within this cube, and helps to reduce the overall state space.

Since this is a 3D maze, we are allowing the agent to maneuver in a 3D manner. Thus, its actions consist of the following: right, left, forward, backwards, up, down. Unfortunately, because of the way Minecraft works, there is no simple command to move up and down freely in water via Malmo commands. If the agent is not always standing on some block, it may begin to sink, which could be potentially harmful to how it updates/learns. We solved this issue by creating multiple floors, so the agent is always ‘grounded’, and can move up and down between levels by using the ‘teleport’ command.

The map features familiar characteristics analogous to the typical reinforcement learning environments. Namely, it contains a start block, end block, obstacles the agent will encounter, and treasures scattered throughout the map the agent can obtain. Treasures are represented as ender pearls and are distributed via a Minecraft ‘dispenser’ mechanism. Obstacles consist of maze-like structures (which are built from sea_lanterns and glow_stones to allow clear, underwater vision), as well as the idea of running out of air. Air pockets (made from wooden doors) are placed randomly throughout levels to allow the agent to explore depth. It should also be noted that in order to make for a more intriguing learner, we decided not to make the mazes on each floor consistent (i.e. at a position (x,y) on the first floor, a wall may be present, but at the same position (x,y) on the second floor, a wall may be non-existent). This limits the actions our agent can take given a particular state, so we constructed an ‘observation grid’ for our agent in order to make sure that we can teleport up/down each floor level.

As our agent explores the maze, it can come across three different types of rewards: receiving an ender pearl (+10 points), finding an air pocket (+10 if the agent is ‘low’ on air, +5 is the agent has ‘medium’ air, and -1 if the agent has ‘a high’ amount of air), as well as finding its goal state, the redstone_block (+100). We assign the agent different rewards for finding an air pocket based off how much air it has left in order to encourage it not only visit an air pocket when it truly needs it. In addition, in order to encourage the agent to find the goal state more quickly (which is located on the bottom-most floor), we decided to give it -1 reward for every step it takes, and +1 reward when it moves down a floor level.

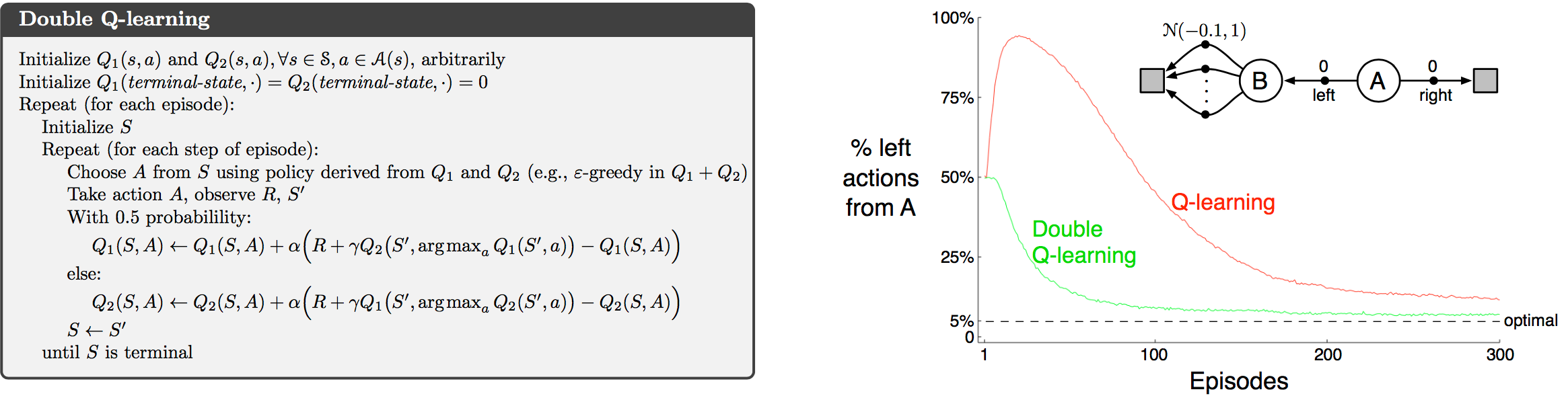

As one of the first breakthroughs in reinforcement learning, the Q-learning algorithm has very unique and interesting properties (Watkins, 1989), which made it an easy choice for the basis of our project. With this in mind, we decided to do some research on different approaches to the Q-learning algorithm. We soon came across the method of ‘Double Q-Learning’ and found that it would fit nicely with the idea of our project. Double Q-learning is just what it sounds like, it’s using two Q-tables instead of just one. However, the advantages are rather intriguing; by separating out reward values into two separate Q-tables, we can inherently separate the value of a state from the value of an action taken to get there. Thus, one Q-table will essentially represent the value of a given state (independent of action), and the other will represent the value of an action given a particular state. This is beneficial for the framework of our project because choosing a particular action may not necessarily be as important as the value of the state itself. For instance, the amount of air our agent has is constantly depleting, and depending on how much air it has left (which is included in the description of its current state), it may choose to travel to a nearby air space, or to simply ignore it and continue exploring other areas in more depth. And though we may find that taking a step forward leads us to an air pocket, if we happen to have a large amount of air left, going to the space may essentially be a waste of time. Thus, its current state may be more beneficial in determining what to do next versus where a particular action takes it.

Though Double Q-learning does not guarantee for the agent to converge any more quickly, it does allow it to process complex state spaces more efficiently. One of the key differences between this method and using a single Q-table is that when choosing an action, instead of choosing the maximum action with probability (1-epsilon), we average over the values of both of the Q-tables, and take the maximum value from the results. By separating out values and averaging among them, this process helps to correct the single Q-learning algorithm’s tendencies to overestimate the optimal action choice. In other words, single Q-learning tends to lead to a maximization bias. Another difference is that when updating the Q-tables, we randomly choose to update only one on each round (each have a 50% probability). Overall, we believe this method will allow our agent to better analyze the environment in which it’s placed.

Q-learning algorithm

Double Q-learning algorithm

Evaluation

Quantitative

In order to evaluate our project in a quantitative manner, we analyzed the rewards that we were receiving at each episode, and made sure that each Q table was correctly computing those rewards. Intuitively, we know that if our rewards our increasing with each consecutive mission, and the difference in consecutive rewards is not too large (i.e. reward values are not random and there is some consistency to them), then our agent is learning something useful. An episode, in our case, ends when either the agent dies from running out of breath, running out of time (which we set to 100 seconds), or when the agent reaches the end goal (the redstone block). We can view a sample of missions and the respective rewards received at each below:

- REWARD FOR MISSION 0: -208.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 1: -240.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 2: -241.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 3: -139.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 4: -217.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 5: -181.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 6: -163.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 7: -145.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 8: -168.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 9: -81.0 <——— reached the redstone block!

- REWARD FOR MISSION 10: -165.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 11: -140.0

- REWARD FOR MISSION 12: -142.0

- . . .

With the above, we can see that our agent begins receiving rewards in the negative 200s, but that soon decreases into the negative 100s, and eventually the agent is able to find a redstone block, where the reward decrease even further (specifically, to -81). Afterwards, the agent continues receiving rewards in the 100s again, but even so, it appears that it is still decreasing in some manner. We assume the latter is due to the fact that is exploring other areas of the maze, and perhaps different routes to arrive at the redstone block again. Regardless, from the above data, we can confirm that our agent is learning how to maximize its rewards.

Another way in which we were able to evaluate our agent, quantitatively, was by observing how long it was able to stay alive per mission. If the agent is dying rather early (before times runs out), then we know it most likely wasn’t able to sustain the amount of air it had very well. On the other hand, if the agent stays alive for a relatively long time, or dies from running out of time, then it was most likely to have found air in a sufficient manner.

We expected for the agent to have a rather short life span in beginning missions, then to increase this time span as it learns how to properly maintain its breath. However, as it nears convergence, we expected the agent to begin decreasing the amount time spent per mission again, which would signify that it has learned a quicker path to maximize its rewards and reach the final goal. Below, we can view a sample of how long the agent is spending in each mission.

- TimeAlive FOR MISSION 0: 2108

- TimeAlive FOR MISSION 1: 4311

- TimeAlive FOR MISSION 2: 5518

- . . .

The results were more or less what we expected. It begins starting off with short life spans, which begins increasing over time. Due to technical difficulties (which we plan on fixing before our final project), our agent had troubles converging, and so we weren’t able to observe if the agent would start decreasing the amount of time spent per mission near convergence. In the future, we plan to supply the agent with a reward that is dependent upon how long it took them to find the final goal.

Overall, if the agent is able to both increase the amount of time it stays alive by sustaining the appropriate amount of air as well increasing the amount of rewards it receives per mission, we are satisfied in knowing that our agent is moving towards convergence and finding an optimal policy. And with the information that we have been able to gather thus far, we believe it is doing just that.

As a last note, we currently have alpha set to a high value so as to promote a high learning rate for the agent. Gamma is also set to a rather high value (approximately 0.7 as of now) so that the agent may favor future results over immediate ones. This is mainly because exploring new depths in this type of environment is a good thing; it could lead to finding more items and potential rewards. Both of these values have allowed us to observe the agent completing missions more quickly (which we hope is a sign that will better lead us to optimal values for convergence). In regards to the epsilon value, we are satisfied with keeping it around a value of 0.1, as that appears to be a common tactic in reinforcement learning in order to prevent the agent from acting ‘too’ randomly. Regardless, we plan on monitoring all of these values more closely in the future.

Qualitative

In order to evaluate our agent in a qualitative manner, we physically observed the agent moving (i.e. watching the agent move around in the Minecraft video window), and made sure, visually, that it was performing to our expectations.

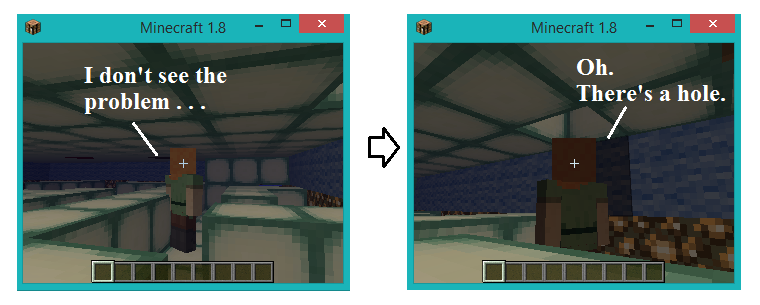

One basis for our observations was to verify that our agent wasn’t having any glitches in its actions. Since we were using the teleportation command to simulate the up/down movement of our agent, we needed to make sure that it was being transferred correctly. At times, we would witness the agent being pierced during teleportation commands (i.e. it would get stuck in a wall or a floor block and suffocate to death); this obviously had negative effects on our updates/learning process. We fixed this by monitoring our ‘observation grid’ more closely and confirming that the way in which we were calculating the agent’s new position was correct by printing out the agent’s current state, as well as its expected state. However, even with this, we still came across similar errors. We finally realized that our agent was processing actions choices and movements too quickly, and increased the amount of ticks (the unit that determines how quickly the agent moves) to 150. After doing so, our agent never came across the problem again.

We also manually observed the agent’s health bar and the amount of air they had left. If we noticed that the agent traveled over an air pocket, we would expect the agent’s amount of air to be fully replenished; if we saw that it wasn’t, then we knew we had some error in our code. In a similar way, we observed the agent’s health bar. If the agent was receiving damage, or if it’s health was not steadily increasing when it still had some amount of air left, then we knew there was most likely some glitch in the environment that we created. At times, we did come across these issues, and had to explore our environment manually (in creative mode) to make sure that all the levels were consistent in height and contained the correct items/block types. For instance, one issue we had was that there was a hole in one of the floors we had built. The agent would proceed to sink down into this hole while calculating its next move, and would incorrectly move into some block, be pierced, and suffocate to death. At first, our agent was moving so fast that we couldn’t detect this problem, but after increasing the amount of ticks, we realized the issue and quickly filled up the hole.

As a final note, there were times when the agent would turn a corner or step inside a narrow path, and the perspective of the camera would close up on the back of the agent’s head, disallowing us to view the surrounding area. This didn’t impeded us from making necessary observations and evaluations, but in the future, we would like to fix the perspective of the camera so that we can always view the general area in which the agent is standing.

Remaining Goals and Challenges

Some goals we are interested in tackling during the remaining weeks consist of expanding the depth of our environment (for instance, increasing the amount of floor levels to six, versus the two that we currently have), as well as removing all the underwater air pockets, in exception to the one it starts at. That is to say, we want to create a more realistic environment for our agent, such that when it beings to run out of breath, it must return to its initial position (i.e. the surface of the water), in order to regain its breath and then continue exploring. We realize that both of these changes will introduce quite a bit of complexity for our agent, and so in order to solve this dilemma, we are going to implement a function approximator to further aid our agent.

We initially had thought of doing some form of function approximation methods such as a neural network, linear approximation and etc. However, after some more research and meetings with the teaching assistant, we’ve come to realize that our initial ideas were a bit overkill for the problem. While the ideas of using a neural network seem very appealing and exciting, the sheer amount of time needed to understand and produce a functioning prototype may be beyond the amount of time we have for this project. And though we will peek into and try our hand at the possibilities of being able to construct one, our main goal will consist of creating a more simple function approximator that computes target rewards in reference to the distances of nearby items (specifically, Euclidean distances). This doesn’t mean we are going to provide the agent with an entire layout of the environment, but we are going to extend its length of ‘vision’.

Right now, we consider our project to be limited in these sense that it has not successfully converged to an optimal policy (though, it has been able to reach the goal state in a small amount of episodes). We believe this is most likely due from a lack of testing. From our analysis, we can see that the agent (despite following along well with double q-learning) still takes some unnecessary actions that yield no, real additional information. For example, given an episode in the initial rounds, the agent will take a path to previously visited location with no treasures or pockets of air and just randomly walk and get stuck in that particular location for an extended period of time instead of going to exploring more treasures. This would seem to indicate that the amount of data currently being gathered is too much for the agent to handle, which is where our function approximation comes in. Rather than taking essentially useless actions, our function approximator will help target distances to items the agent may have otherwise ignored, and will alleviate the overall problem our agent has with taking unnecessary explorations of previously visited states.

Given our experiences thus far, we anticipate the problems that will arise by the time the final report is due are that thinking of an idea and implementing it may encompass many more problems that one might expect. While ideas are simple to state, there are many problem that arise when the combination of so many different technologies are involved. We’ve realized that now after finally becoming somewhat familiar with the Malmo API. While we don’t know for certain how crippling this problem might be, we believe we’ve taken the necessary precautions to maximize our chances of completing our goal; namely, focusing our time on a function approximator that is not as complex as a neural network. We do expect problems to arise with the more relatively simple function approximator but expect that by reducing the complexity of the proposed method, the problems that arise should be doable in the time allotted to us.

In conclusion, the remaining goals and challenges we have for remaining days till the final submission are to make the necessary modifications to make our prototype fully functional (i.e. making it converge), as well as creating a more realistic environment for the agent (by increasing depth complexity, though this will be alleviated via a function approximator). We are going to perform more profound measurements and observations (such as plots and graphs to get a better visualization of the data) once we are able to obtain a more abundant and sufficient amount of said data. We believe our goals are reasonable to accomplish with the remaining time, and are excited to watch our agent grow in the coming weeks!

References

- Watkins, C. J. C. H., Dayan, P. (1992). Q-learning. Machine Learning, 8:279–292.

- Double Q-learning research article

- Double Q-learning Summary

- Dueling Deep Q-Networks article

- Deep Q-Networks blog